Jonas Mekas: the Enlightenment of Andy Warhol

Behind a powerful and shiny man, there must be someone he wants to imitate.

A lot of times we can't just see the awesome

behind the amazing

there is always an enlightened

they stand on their teacher's shoulder and look at the world

and we stand on their shoulder

I wish we could see a different view

Jonas Mecas, taken at the Classic Film Archive, New York City, November 2012. Photo: Anne Collins, a reporter from the Observer

Jonas Meckas will be 90 years old on Christmas Eve, and he still remembers what happened at the age of six: he was sitting on his father's bed, singing a strange little song about daily life in the Lithuanian village where he was born.

"it was the stillness of the night, and the scene suddenly came to mind, and what I saw and heard on the farm that day was still fresh in my mind. It's just a very simple, real daily routine. The recollection is real, and there is absolutely no element of fiction mixed with it. The warm voice and smile of my parents still haunts me. However, I also remember that the feelings in my heart were burning when I described the details of my father's daily affairs. Since then, I have been trying to seek this strong feeling from my work. "

in the spacious studio in Mekas, Brooklyn, we sat at a table in the kitchenette area, over which hung a faded old picture of Altir Rambo. This photo is one of Mekas's constant inspiration. Around us, piles of boxes filled with archives piled up, filling every inch of space within reach: printed materials, diaries, film, letters, essays-all showing the passionate everyday life incisively and vividly.

the character, known as the Godfather of avant-garde movies, is about to usher in a long-awaited moment. On December 5, an exhibition of his personal works will be held at the Snake Gallery in London. Meanwhile, the British Film Association in London's South Bank will hold a retrospective of his major films and video logs, while the Pompidou Art Centre in Paris will launch a film season on December 30 to celebrate his life and achievements. "I have reached the pinnacle of my life and achieved fame, so I have no regrets in this life," he laughs.

Mekas is an indispensable figure in the history of avant-garde films (formerly known as underground films). He acts not only as a filmmaker, but also as a writer, planner and catalyst. With his help, the Classical Film Archive was established in New York in 1969, which houses the most extensive existing experimental film materials, and he has been responsible for overseeing the restoration of many classic films ever since. From time to time, he mentions the famous people who worked with him during the golden age of avant-garde filmmaking in the 1960s, from Yoko Ono to Jacqueline Kennedy and Alan Ginsburg, from the beat Generation to the Warhol series. Many of these characters are involved in his films, which in turn affects characters like Jim Jamushi, Hamoni Colin, John Vorster and Mike Fergis.

You'll be turning heads with our magical colelction of plus size wedding dresses with sleeves. These are the best options for the big day.

Mekas's works are not only full of personality, but also arbitrary and unpredictable. In view of his long experience in Lithuania in his youth, he has seen all kinds of life and tasted the warmth of the world. Perhaps it is reasonable that his works tend to awaken deep memories and life experiences. Fashion designer Anyasbe, his bosom friend and supporter, described him as an "artist, writer and memory", an unforgettable comment.

for an 89-year-old man, Mekas has an immutable quality, always unruly, unruly, and childlike stubbornness, but it is his playfulness and mischief that has driven him to push forward his work in a serious manner for more than 60 years, and he is still fruitful. The maverick filmmaker Hamoni Colin summed up his unique temperament: "Jonas is the real hero of the underground cinema, the number one radical-a shapeshifter, an epoch-making figure." He has insight into things that no one else can touch. His films awaken memories, illuminate the soul, and are full of tenderness and emotion. No one can match it, and his films will be immortal. "

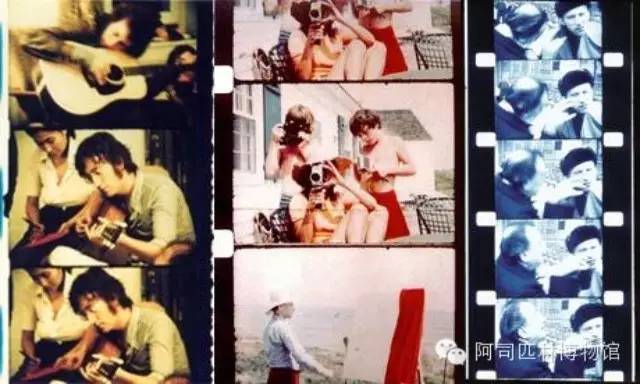

his films are biographical journals in Impressionist style to some extent. Without the drama of ups and downs and suspense, rejecting storytelling and linear narration, Mex prefers to describe what he calls "depicting subtle intimate moments in plain everyday reality." His art is embodied in jumping clips and fleeting, constantly switching pictures, often capturing dim colors with a Polex 16mm camera and weaving moments and layers of memory into documentary scenes.

Mekas himself is naughty, dressed in a blue work coat and a blue hat, his eyes are half-closed and half-open, and he looks sleepy until he stares at you with keen eyes. He was born in a small village in northern Lithuania on December 24, 1922. This place, he said, "used to be calm and the world was peaceful, but then there was a lot of disaster and rough seas." In his childhood, he contracted a mysterious disease, which made him so skinny and haggard that local boys nicknamed him "death". As a result, he plunged into the sea of books and wrote his personal diary like an obsession. He was only 17 years old when Soviet tanks entered Lithuania in 1940. He hid behind a wall in the village and began to photograph the scene with his first camera, but he didn't see the actual effect. A Russian soldier stormed the camera and confiscated the film. "everything has changed since the Russians came," he said now. "our farming system, our way of life, everything has been wiped out."

1941When the German army invaded Lithuania in 2008, Mekas joined the resistance, helping to publish regular secret news bulletins collected from BBC radio broadcasts. When his typewriter mysteriously disappeared, he buried his diary in a field and fled to Vienna with his brother Adolfas, lest the authorities track him through typewriters and send him to a labor camp to serve his sentence or even more severe punishment.

they were caught on the run and then sent to a labor camp near Hamburg, where they managed to escape after eight months and then hid in a barn near the Danish border. At the end of the war, they wandered from place to place, moving from camp to camp for two years in a row. "We pass the time by watching shoddy American movies," he said. "We gradually feel bored and foggy, and we don't know where the future lies."

in 1949, he and his brother moved to the United States, and their lives changed dramatically again. They live in a dilapidated house in Williamsburg, Brooklyn, are open to any job they find, and have made huge signboards for Pepsi. An April 1950 diary was reproduced in his book "I have nowhere to go", which read: "Life goes on." It was business as usual, but we were very busy. Tossing from factory to factory, indulging in an obsession with movies. We joined several exploratory film clubs just to feel the pulse of the times and make more friends. We even show them some movie scenes. "

how did he make a leap from watching movies to making movies? I was 27 years old and I had to make up for all the time I wasted in the refugee camp, so I began to absorb all kinds of things. I go to the cinema every day. I am hungry for culture and eager for excitement. This means racing against time, cherishing time like gold, and after years of doing nothing, we are bound to make some achievements. When I opened my eyes and broadened my horizons, I just realized that this was only a small step towards my film career.

Mekas' son Sebastian came to the studio. They chatted for a while, and then a young assistant appeared. He silently walked into a corner of the pile of boxes and began to work. Jonas took a bottle of water from the refrigerator and went on to describe his wonderful life story. He told me that two weeks after arriving in New York, he used a loan to buy his first Polex camera. He was inspired by the avant-garde films shown by the 16 Film Association at the Amos Vergil Cinema, where avant-garde films by the great Ukrainian filmmaker Mia Darren are often shown.

at first, Mekas filmed the life of the Lithuanian community in Brooklyn. (some of the scenes appeared in the 1976 film lost.) back then, he said, he was still eager to recall his overseas exile. "the memory of my hometown is still fresh in my mind, but then when I was immersed in the other scene and ignited by the emerging creative spark, the feeling of exile gradually disappeared."

soon after, he began showing his short films in small galleries in the East Village and the Lower East side of Manhattan. Then, in the spring of 1955, he officially moved to Manhattan across the Brooklyn Bridge and began photographing the new people he met, absorbing new energy from the air. "it was really the beginning of my new life," he said. "people say I am ill-fated, but I always say I am glad to have experienced a life of displacement and displacement." I was forced to enter New York at a time when all new energies and ideas are springing up like bamboo shoots after a spring rain, showing an atmosphere of letting a hundred flowers blossom and a hundred schools of thought contend, a trend not only in the film industry, but also in the fields of literature, art and music.

in New York, Mekas was nurtured by the avant-garde culture led by artists, writers, musicians, photographers and filmmakers. He often ran into characters like Allen Ginsburg, filmmaker Meyadelen, Robert Frank, John Cage and musician Lamont Young, who came to his Manhattan attic to celebrate conventional movie nights. In 1954, he and Adolfas founded the Film Culture Magazine, which commented on various forms of films, but mainly focused on the field of avant-garde films. The main editors include director Peter Bogdanovich (who then directed the Last Film), experimental filmmaker Stan Brahag and critic Andrew Saris.

meanwhile, Mekas began to write a movie column for the film magazine country Voice. Then, in 1962, he co-founded the filmmakers' cooperative and began to show independent films regularly in the filmmaker's experimental cinema in 1964. The two joint ventures laid the foundation for the establishment of the classic film database. The database is dedicated to the preservation and projection of experimental films.

"almost everything I create or help create is done out of necessity," Mekas said. "for example, Film Culture magazine was founded because we get together regularly to discuss films, but we are unable to express ourselves, unlike the British" Audiovisual Magazine "or the French" Film Handbook ". For filmmakers to speak freely. This is the same as the screening. I started the organization only because there are too many films to be shown. When we started showing these films, I had to post the screening message in advance in the column of country Voice. Everything is out of necessity.

in 1961, Mekas also made his first feature-length film, "A hail of bullets," which he tried to make in a traditional film narrative. "the film cost $15000, and it was a lot of money at the time," he said, still frustrated. "this is the only time I have encountered financial difficulties in my career, and I struggled because I went astray." His next film, the brig, is based onA sad drama of the same name, about a day in a military prison, cost $900. Although the film features actors and scripted scenes, it won the jury award for best documentary at the Venice Film Festival in 1964 for such realistic pictures. The Movie Handbook begins with a positive comment: "after watching this film, people swear not to see it again." This is because it is impossible for them to see such a magnificent sight twice. "

in 1964, Mekas successively screened Jack Smith's "Blood creation" and Jean Genet's "Love Song", the former involving explicit sex scenes and the latter depicting homosexual scenes. He was subsequently arrested for spreading obscenity. In the same year, he helped Andy Warhol shoot some of the movie scenes that eventually led to the Matrix. Pop artists are now famous for their silent slow motion and eight-hour meditation images that have almost changed the impression of the Empire State Building.

Mekas holds regular impromptu nights in the Manhattan attic, where Warhol becomes a regular visitor. When I was invited to the party of Naomi Levin (one of Warhol's "superstars"), I realized that he was the white-haired guy sitting on the floor watching my movie, and then we became friends. I always remember when we went together to see Lamont Yang's performance, in which a note lasted for four or five hours. Soon after, I helped Andy shoot Matrix. Yang is responsible for stretching the timeline of voice signals; Andy has mastered the concept to achieve visual reproduction. "

Mekas also supported the underground velvet band, allowing them to rehearse in his attic; in January 1966, the band gave their famous performance at an event held by the New York Clinical Psychiatric Association at the Delmonigo Hotel in New York. He filmed the occasion. According to legend, it was Mekas and his friend Barbara Rubin, an experimental filmmaker, who introduced Warhol to Ludwig.

Jonas Mekas Photography (from left): John Lennon and Yoko Ono sing birthday songs for John, 1996; Jackie Onarcis and her children, from Paradise on Earth, 1999; Mekas and Salvador Dali, from the Dilemma, 1978. Copyright: Jonas Mecas

El Dali was another regular in the attic during that period. According to Mecas, "he realized that he needed to get in touch with the younger generation and understand the pulse of New York at that time." Mekas remembers that when Dali "walked up the stairs to my floor, there would be rubbing footsteps in the hallway," and they agreed that Mekas should shoot impromptu street art by one of the artists. On April 18, 1964, Mecas filmed the work scene of El Dali: model Vincuska was tied up in the street by the grinning Mecas and then put on shaving cream by Dali.

perhaps even more surprising is Mekas's friendship with former first lady Jacqueline Kennedy, who was introduced by Peter Bild, an artist, photographer and socialite. For a time, he tutored her children John and Caroline in film production. "I spent a few summers in their Montauk house," he said with a smile. "I compiled a small manual for their reference and assigned them all kinds of exercises." It seems that John Kennedy Jr. instinctively mastered the method taught by Mekas. "I remember that he won the school award for his multi-screen diary film about summer life."

Mekas also remembers that at the Family gathering on Mother's Day, Jackie Kennedy showed his film Walden: diaries, notes and sketches about the avant-garde art scene of the 1960s. How did they react? "she cried, and they all cried," he said. "it's a good response." For a time, Jackie wanted Mekas to make a film about her life. He spent more than a year collecting homemade films, family photos and video footage of her and her late husband. "and then her friends from the TV station got involved, like, 'who is this guy? We have never heard of him.' They put a lot of pressure on her and things got awkward, so I chose to quit, but we remained friends. "

in 1999, Mekas released the film Paradise on Earth, a 35-minute 16mm film that revolves around the summers spent with Jackie, her children and his sister Lacheville in Montauk, followed by a similar diary film about George Mahinas, founder of the Lithuanian wave art movement and John Lennon and Yoko Ono. Mekas and Yoko Ono also became friends in New York.

"I met Yoko through George Messinas as early as 1962," he said. "her first exhibitions were under way. I also helped her move, and I kept in touch with her when she returned to Japan and suffered from a nervous breakdown. " In order to help her return to the United States, Mekas even arranged a fictitious position for Yoko in the Film and Culture Magazine. John and Yoko arrived in the United States in 1976 and decided to settle there. Mekas was the first person to call to tell them the good news. "it was late at night and I had already gone to bed when suddenly I received a call from Yoko, who had just landed at Kennedy International Airport. She said, 'Jonas, John wants you to have an espresso. Do you know that New York is still a good place to do business?' It sounds crazy, but this is the real scene at the time. I took them to the coffee shop that I knew was open until early in the morning, and John had a cup of espresso and a cup of Irish coffee. I can tell you that he enjoyed his coffee on his first night in the United States. "

Mekas for those iconicThe short film made by the characters is a glimpse at the peak of the avant-garde film. From the rise of the seclusion movement in the mid-1950s to the rapid development of the hippie counterculture movement in the United States a decade later, then in the 1970s, Mekas was at the vanguard of that revolution. He is famous for personalized films such as Memoirs of Journey to Lithuania (1971-72) and lost (1976), which are made up of six videos. It covers his life after his arrival in New York and his interactions with characters such as Robert Frank, Leroy Jones and the dreamy singer Tenny Tim.

fighting alongside Stan Brahag, Meyer Darren, and Kenneth Angel, Mekas challenged the commercial orthodoxy and traditional story layout of the Hollywood studio system through maverick and unrestrained meditation. although when I used the word "experimental", Mekas immediately rejected it. "No one is doing an experiment, not Meya, not Stan Brahag, and certainly not me. We make different types of movies because we are driven by reality, but we don't think we are experimenting. Let's leave the experiment to the scientists. "

it is very important to recognize that what we are doing is not art. I'm just a filmmaker. I live in my own way, do my part, and record the moments of my life on my way forward. I did it because of the circumstances. Necessity rather than artistry is the real route I need to follow in my life and work.

however, it turns out that Mekas has never considered competing with traditional movies. "We just want to do something else to keep pace with Hollywood, but they don't want to accept us. They have built layers of indestructible walls around traditional films, so we have to find ways to survive and develop outside the walls. "

he told me that although talented food filmmakers were also tireless promoters of avant-garde films, Meyadelen could only show her films in 15 university venues in 1960. By 1970, the number of college film venues had increased to 12000. Mekas and his brother Adolfas are the main catalysts for this cultural upheaval.

just as I was about to leave, Mekas gave me a CD-ROM copy of the Sleepless Night Story, one of his recent activities. It is a film formed by the convergence of some recent series moments. The flashing close-ups on the screen featured familiar faces-Marina Abramovich, Patty Smith, Louis Burchoa-as well as unfamiliar faces. It is a reflection on love, memory, friendship and loneliness. "think back to the moment when you wrapped a gift for a friend or opened a gift from a friend," says Mekas, one of the recurring images in the film. "what I am exploring now is the essence of those ordinary moments, that is, the strong feelings contained in them. That's what I've been trying to explore all these years. In fact, I am an anthropologist dedicated to exploring these meaningful moments. "

at the end of our conversation, I asked him what he thought of contemporary culture and how it was different from the creative anti-traditionalism movement he was involved in in New York in the 1950s and 1960s. He thought for a moment and then replied. "when the old form begins to disintegrate because of the impact and dying struggle, a new idea will emerge as the times require. That's because of the situation at that time, and maybe it's still working now. " He told me about his understanding of Joseph Conrad's concept of light and shadow underlining: the great cultural changes that took place from time to time swept away all the decadent and outdated things.

"it's out of date," he said solemnly, "but I think the light and shadow line is in decline and new things are beginning to be born. New content requires new forms and new technologies. That is the basis for the survival and development of the Internet and digital technology. We have repeatedly used the same old method for 40 years in a row, so it is necessary to replace it with a new one. Necessity is the key. " He stood up and shook my hand. "I've always been hopeful," he said with a smile.